esophageal speech

Want to learn more about Esophageal Speech?

|

|

|

|

SELF HELP FOR THE LaryNGECTOMee

|

The Original by Col. Edmund Lauder, a SLP and laryngectomee.

Covers a wide range of material on adjustment and rehabilitation, speech methods and exercises, support groups and more. Also includes ads which are valuable reference to many useful products.

|

|

Esophageal Speech Samples

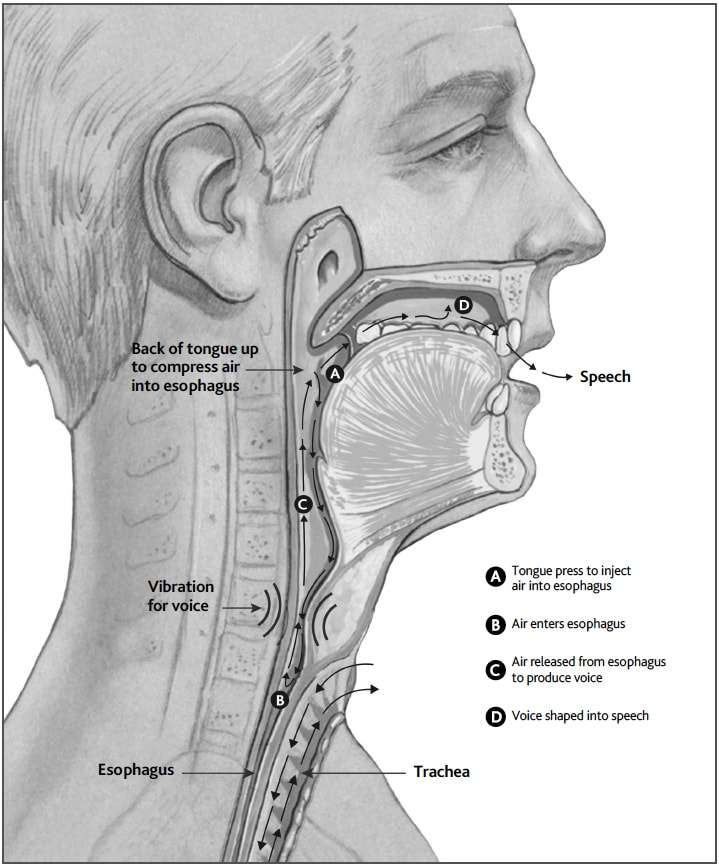

Speech produced by trapping air in the esophagus and forcing it out again. It is used after removal of a person's larynx (voice box). Click on the Links below to hear samples of esophageal speech: (*Sample provided courtesy of Dr. Philip C. Doyle, Voice Production and Perception Laboratory, University of Western Ontario), from http://www.webwhispers.org/library/EsophagealSpeech.asp |

Questions? Just call us or watch our educational movieclips on Youtube: The Servox Guru.

SPEAKING ESOPHAGEALLY BY JIM SHANKS, PH.D.

This was written for and published in Whispers on the Web, March 2005

This message is intended for a limited audience: 1) the individual laryngectomee who does not have access to a qualified teacher of post-laryngectomy speech, and 2) the individual speech-language pathologist (SLP) who has not had special instruction in all three voice options for speech after laryngectomy. The message focuses on esophageal speech (ES). Although you can learn to ride a bike without knowing how it was built or works, the following explanation is offered to all 'bike riders'.

We know that laryngectomy surgery means: no voice box - no voice. Historically, ES was the primary or only choice for many decades after laryngectomy surgery became successful in saving lives. To the quantity of life should be added quality of life. To be without voice or speech is a tragic circumstance. One has to be haunted by the tale of a man from western Indiana who had his operation in St. Louis. At his post-op visit, the patient was told by his surgeon that although he (the doctor) did not know what was involved, he understood that there was a way of learning to speak again. After the Hoosier came home, every day he silently tried to form words. After 6 months, as a burp came up, the man said a word, then toiled to imitate his chance sound. When he was able to count to ten out loud, he went to bed to have the best sleep he'd had in half a year!

Getting Air In!

For those who have the good fortune of not undergoing laryngectomy, to talk involves using air power to drive vocal cords in the voice box, or larynx. This cord action is like the sound of the 'Bronx cheer' (raspberry). Lung air can be pushed out from the mouth between lips half together with some tension. This sound is voiced, has pitch and loudness.

Whereas the lungs can hold 4,000-6,000 cc of air, the food tube (esophagus), holds only 100 cc. This dinky tube, running up and down behind the wind pipe (trachea), can serve as a substitute storage tank for air. Usually the tank has only a small bubble of air (taken in while swallowing food or from gas-producing food). In order to serve as a new lung, it is necessary to move air down from the throat into the esophagus. At the top of the esophagus is a ring of muscle that is usually closed tight. This muscle ring serves as a cap on the gas tank that is the esophagus. Gas getting into a car's tank goes only 1 way: down. Likewise, food going through the esophagus into the stomach goes only down. Getting air into the esophagus is not so simple. Getting air into the esophageal tank may be by either of two ways: inhaling or injecting. You can even think of it as kissing or spitting at the lips. We think there are more spitters, but many of us prefer kisses. It's hard to do both at the same time! Esophageal speakers may be divided into inhalers or injectors. The key: where is the pressure to fill the tank. Inhalers have negative pressure below to pull air in. Injectors have positive pressure above to push air into the esophagus.

Bringing air up and out from the esophagus actually generates esophageal voice. But the real problem is getting air in first. To help a person feel air being sucked in (as the inhalers do), we may consider parallel actions. To hiccup is one example. To sniff is another. To yawn is yet another. To gasp is another. Breathing air into the lungs may parallel breathing (i.e., inhaling) air into the esophagus. This is facilitated by first exhaling lung air, then raising the head and chin while inhaling. A smoker may imitate getting a 'drag' on a cigarette/pipe/cigar. Achieving esophageal inhalation involves two different acts: (1) reducing the tension of the muscle ring at the top of the esophagus, and (2) further lowering the pressure within the esophagus. Pressure within the esophagus is negative at rest and varies with pulmonary respiration, becoming more negative when the lungs inhale air. This greater negative pressure literally sucks air from the throat down into the esophagus - assuming one can get the muscle ring at the top of the esophagus to open up!

The injector uses a different scheme to force air from the throat down into the esophagus using the lips and/or tongue. An obvious action that one might think is parallel is swallowing. In the old days a 'new' laryngectomee might have a glass of water to sip. Water is a fine product - for bathing, wetting one's mouth, getting food to move south. However, swallowing is not the same as injecting air into the esophagus for speech purposes. For one thing swallowing involves much greater pressures along the length of the vocal tract from the tongue tip to the bottom of the throat. Additionally, when one swallows food, the esophagus is quite intent on moving the material all the way down its length and into the stomach, usually a 'point of no return'. If the intent is to get air into the esophagus, one might think about swallowing carbonated liquid (beer, soda pop) or eating gas-generating foods (cabbage, beans). There are similar problems with this approach. To create air in the stomach from carbonated drinks or gas-generating foods is not the same as injecting air just part-way down the esophagus. We want air to enter the esophagus, but not proceed to the stomach. While a savvy esophageal speaker can take advantage of air that inadvertently made it to the stomach and plans its own return, one is better able to control the return of air if it never descends further than, say, the upper to middle part of the esophagus (Also, we won't go into other horror stories involving carbonated beverages, beans, and cabbage: having beer for breakfast, feeding beer to a recovered alcoholic!)

Raising pressure in the throat may be facilitated by: puffing out the checks, whistling, whispering, blowing out a match, trying to blow up a balloon or manometer, blowing the nose, swallowing while holding the nose (a Valsalva), 'starting' to swallow, or saying speech sounds (p, t, k, f, s, sh, ch) which are voiceless consonants involving increased air pressure from the mouth. Some people learn to 'burp' as children or to relieve excess stomach air. Seldom do we find people trying to pump air into the mouth/throat, as with a tire pump or an inflated balloon. Inhaling is apt to be accompanied by raising, injecting by lowering, the head.

Getting Air Out!

Having gotten air into the esophagus, one might assume that it is a simple matter to release the cap on the gas tank for voice. Not so. Mother Nature doesn't like to be fooled. She tells the body to push down on contents from the esophagus into the stomach, like milking a cow. Putting milk up into the udder is not so easy (vomiting is the exception!)

The diaphragm is a muscle for inhalation - breathing air into the lungs. Opposing it in exhalation are abdominal muscles (running up and down in front of the belly) which squeeze in from below to force air out of the lungs. For esophageal speakers, abdominals also are responsible for pushing speech air up and out - but this time out of the esophagus. In fact, good esophageal speakers use less vocal volume and muscle effort than a non-laryngectomee using the diaphragm. Some laryngectomees think that they can talk while 'holding their breath' but it can't be done!

Esophageal voice can be identified/described in three ways: pitch/frequency, loudness/intensity, and rate/time. The first letter of the second term makes a word. 'FIT'. This acronym has been discussed elsewhere.* Perhaps the concern of getting a voice causes us to think that once a voice is acquired, nothing more is needed. Not so! Speech must be understood as well as heard! Good esophageal speakers are able to manipulate the 'F' (frequency), 'I' (intensity), and 'T' (time they are able to produce esophageal sound).

To change voice into speech involves letting the 'Bronx cheer' from the top of the esophagus vibrate (or resonate) through three cavities: throat, mouth and/or nose. Lips and tongue are then moved to articulate individual sounds. Without getting technical about every speech sound, we should agree on how to judge speech. Vowel sounds (15-25) outnumber vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u and sometimes y). In esophageal speech, vowel sounds usually are understood, even as accents. Only when significant damage has been done (i.e., to the tongue) will there be errors.

However, boo-boos occur too often on consonants in esophageal speech. Here we address only the main errors to be expected. If we are not careful, we may lose some hiss in sounds like 's' and 'sh'. The 'hiss' or noise is what gives these consonants their characteristic sound - without it, a listener may detect a sound other than the one intended by the esophageal speaker. Some consonants are voiceless (p, t, k, f, s, sh, ch, h, and th as in thumb). However, the very voice we sought can be over-done, thus distorting the voiceless into a voiced consonant (p, t, k, f, s, and sh become b, d, g, v, z, and zh). For those with a larynx, the difference between a voiced or voiceless consonant can be felt by placing a finger on the side of the larynx/voice box while saying the sound. (See previous articles noted below) There's a vibration that can be felt for the voiced, but not the voiceless sounds. When everything becomes voiced (as often happens in esophageal speech), the resulting faulty sound pattern can resemble pseudo bulbar palsy or inebriated speech. Correcting it lies not in dropping voice, but in adding more pressure to the sound emerging from the lips when making the voiceless sounds. When learning esophageal speech, a moist finger, strip of Kleenex or whistle placed at the lips may help the laryngectomee speaker monitor the extent to which pressure is exploded from the mouth when talking. Voiceless consonants have more air power! One nasty voiceless consonant is the 'h' which baffles all laryngectomees. To avoid sounding like a Cockney from England, we borrow from another country. 'I' ('ich' in German) uses a prolonged kiss of the back of tongue against the roof of the mouth. The same sound is in Scotland (loch/lake). We get the same result by saying 'k' as a non-stop prolonged consonant: for the good esophageal speaker, saying the word 'hair' lies between 'air' and 'care'. Finally, three sounds are supposed to go through the nose: 'm, n, ng' as in the word 'morning'. The back part of the mouth (palate) must lower, letting sound and air into the nose to get the nasal tone. Some esophageal speakers don't let the palate down when making 'm, n, ng.' This common error makes the word 'morning' sound like 'bordig.' Again we may invoke a wet finger, this time placed just underneath the nose to feel whether air escapes nasally on these sounds.

What's In Store

The outlook for the continued use of esophageal speech is grim, at least in the United States, but also in many other parts of the world. Esophageal speech is the least utilized form of alaryngeal speech. Although the ES Speaker is less dependent on things - no device to carry, no prosthesis to insert, clean or replace - it takes longer to learn, has limitations of rate (fewer words per minute), takes more time to re-load air for speech, and has fewer physicians and SLP's who recommend it and even fewer who can teach it and trouble shoot problem cases. Although artificial larynx and tracheoesophageal speech (TEP) may cost more, these days, those costs are more apt to be covered by insurance or physician fees than SLP therapy sessions to teach esophageal speech. In addition, the preponderance of TEP success has lead to less teaching of esophageal speech in IAL clubs. Fewer IAL clubs and fewer IAL members portend a shift from peer support to highly specialized intervention.

Support for the continuance or existence of IAL Voice Institutes is eroding. Historically, the IAL Voice Institute has been a primary vehicle for training clinicians and laryngectomees how to train others in esophageal voice use. Few university programs in speech pathology include ES in the curriculum, at least not to the extent needed to prepare clinicians who are both confident and competent in offering this voice option.

Surgical specialization in voice restoration after laryngectomy is becoming a sub-specialty, even within the specialized field of ENT physicians. The role of ES can be expected to diminish more and more, at least in most parts of the world. Perhaps esophageal speech will continue to have a place in certain areas, although even this is not a guarantee.

Although we began with a focus on voices after total laryngectomy, we conclude by stressing speech and communication. This reinforces our goal of helping individuals cope with an unusual problem in living fully. Each of the three primary alaryngeal speech options ' AL, TEP, and ES' has advantages and disadvantages over the others. Although it has become rare given the current direction of alaryngeal voice rehabilitation, there will always be those for whom esophageal speech remains not only a viable option, but perhaps the best option. The question will be whether anyone can teach it to them. Or will they stumble upon it on their own as our Indiana Hoosier did several years ago.

VoicePoints: Are Your Voice And Speech "Fit"? (Part 1 of 2)

http://webwhispers.org/news/feb2004.htm

VoicePoints: Are Your Voice And Speech "Fit"? (Part 2 of 2)

http://webwhispers.org/news/mar2004.htm

Article from http://www.webwhispers.org/library/EsophagealSpeech.asp

This message is intended for a limited audience: 1) the individual laryngectomee who does not have access to a qualified teacher of post-laryngectomy speech, and 2) the individual speech-language pathologist (SLP) who has not had special instruction in all three voice options for speech after laryngectomy. The message focuses on esophageal speech (ES). Although you can learn to ride a bike without knowing how it was built or works, the following explanation is offered to all 'bike riders'.

We know that laryngectomy surgery means: no voice box - no voice. Historically, ES was the primary or only choice for many decades after laryngectomy surgery became successful in saving lives. To the quantity of life should be added quality of life. To be without voice or speech is a tragic circumstance. One has to be haunted by the tale of a man from western Indiana who had his operation in St. Louis. At his post-op visit, the patient was told by his surgeon that although he (the doctor) did not know what was involved, he understood that there was a way of learning to speak again. After the Hoosier came home, every day he silently tried to form words. After 6 months, as a burp came up, the man said a word, then toiled to imitate his chance sound. When he was able to count to ten out loud, he went to bed to have the best sleep he'd had in half a year!

Getting Air In!

For those who have the good fortune of not undergoing laryngectomy, to talk involves using air power to drive vocal cords in the voice box, or larynx. This cord action is like the sound of the 'Bronx cheer' (raspberry). Lung air can be pushed out from the mouth between lips half together with some tension. This sound is voiced, has pitch and loudness.

Whereas the lungs can hold 4,000-6,000 cc of air, the food tube (esophagus), holds only 100 cc. This dinky tube, running up and down behind the wind pipe (trachea), can serve as a substitute storage tank for air. Usually the tank has only a small bubble of air (taken in while swallowing food or from gas-producing food). In order to serve as a new lung, it is necessary to move air down from the throat into the esophagus. At the top of the esophagus is a ring of muscle that is usually closed tight. This muscle ring serves as a cap on the gas tank that is the esophagus. Gas getting into a car's tank goes only 1 way: down. Likewise, food going through the esophagus into the stomach goes only down. Getting air into the esophagus is not so simple. Getting air into the esophageal tank may be by either of two ways: inhaling or injecting. You can even think of it as kissing or spitting at the lips. We think there are more spitters, but many of us prefer kisses. It's hard to do both at the same time! Esophageal speakers may be divided into inhalers or injectors. The key: where is the pressure to fill the tank. Inhalers have negative pressure below to pull air in. Injectors have positive pressure above to push air into the esophagus.

Bringing air up and out from the esophagus actually generates esophageal voice. But the real problem is getting air in first. To help a person feel air being sucked in (as the inhalers do), we may consider parallel actions. To hiccup is one example. To sniff is another. To yawn is yet another. To gasp is another. Breathing air into the lungs may parallel breathing (i.e., inhaling) air into the esophagus. This is facilitated by first exhaling lung air, then raising the head and chin while inhaling. A smoker may imitate getting a 'drag' on a cigarette/pipe/cigar. Achieving esophageal inhalation involves two different acts: (1) reducing the tension of the muscle ring at the top of the esophagus, and (2) further lowering the pressure within the esophagus. Pressure within the esophagus is negative at rest and varies with pulmonary respiration, becoming more negative when the lungs inhale air. This greater negative pressure literally sucks air from the throat down into the esophagus - assuming one can get the muscle ring at the top of the esophagus to open up!

The injector uses a different scheme to force air from the throat down into the esophagus using the lips and/or tongue. An obvious action that one might think is parallel is swallowing. In the old days a 'new' laryngectomee might have a glass of water to sip. Water is a fine product - for bathing, wetting one's mouth, getting food to move south. However, swallowing is not the same as injecting air into the esophagus for speech purposes. For one thing swallowing involves much greater pressures along the length of the vocal tract from the tongue tip to the bottom of the throat. Additionally, when one swallows food, the esophagus is quite intent on moving the material all the way down its length and into the stomach, usually a 'point of no return'. If the intent is to get air into the esophagus, one might think about swallowing carbonated liquid (beer, soda pop) or eating gas-generating foods (cabbage, beans). There are similar problems with this approach. To create air in the stomach from carbonated drinks or gas-generating foods is not the same as injecting air just part-way down the esophagus. We want air to enter the esophagus, but not proceed to the stomach. While a savvy esophageal speaker can take advantage of air that inadvertently made it to the stomach and plans its own return, one is better able to control the return of air if it never descends further than, say, the upper to middle part of the esophagus (Also, we won't go into other horror stories involving carbonated beverages, beans, and cabbage: having beer for breakfast, feeding beer to a recovered alcoholic!)

Raising pressure in the throat may be facilitated by: puffing out the checks, whistling, whispering, blowing out a match, trying to blow up a balloon or manometer, blowing the nose, swallowing while holding the nose (a Valsalva), 'starting' to swallow, or saying speech sounds (p, t, k, f, s, sh, ch) which are voiceless consonants involving increased air pressure from the mouth. Some people learn to 'burp' as children or to relieve excess stomach air. Seldom do we find people trying to pump air into the mouth/throat, as with a tire pump or an inflated balloon. Inhaling is apt to be accompanied by raising, injecting by lowering, the head.

Getting Air Out!

Having gotten air into the esophagus, one might assume that it is a simple matter to release the cap on the gas tank for voice. Not so. Mother Nature doesn't like to be fooled. She tells the body to push down on contents from the esophagus into the stomach, like milking a cow. Putting milk up into the udder is not so easy (vomiting is the exception!)

The diaphragm is a muscle for inhalation - breathing air into the lungs. Opposing it in exhalation are abdominal muscles (running up and down in front of the belly) which squeeze in from below to force air out of the lungs. For esophageal speakers, abdominals also are responsible for pushing speech air up and out - but this time out of the esophagus. In fact, good esophageal speakers use less vocal volume and muscle effort than a non-laryngectomee using the diaphragm. Some laryngectomees think that they can talk while 'holding their breath' but it can't be done!

Esophageal voice can be identified/described in three ways: pitch/frequency, loudness/intensity, and rate/time. The first letter of the second term makes a word. 'FIT'. This acronym has been discussed elsewhere.* Perhaps the concern of getting a voice causes us to think that once a voice is acquired, nothing more is needed. Not so! Speech must be understood as well as heard! Good esophageal speakers are able to manipulate the 'F' (frequency), 'I' (intensity), and 'T' (time they are able to produce esophageal sound).

To change voice into speech involves letting the 'Bronx cheer' from the top of the esophagus vibrate (or resonate) through three cavities: throat, mouth and/or nose. Lips and tongue are then moved to articulate individual sounds. Without getting technical about every speech sound, we should agree on how to judge speech. Vowel sounds (15-25) outnumber vowel letters (a, e, i, o, u and sometimes y). In esophageal speech, vowel sounds usually are understood, even as accents. Only when significant damage has been done (i.e., to the tongue) will there be errors.

However, boo-boos occur too often on consonants in esophageal speech. Here we address only the main errors to be expected. If we are not careful, we may lose some hiss in sounds like 's' and 'sh'. The 'hiss' or noise is what gives these consonants their characteristic sound - without it, a listener may detect a sound other than the one intended by the esophageal speaker. Some consonants are voiceless (p, t, k, f, s, sh, ch, h, and th as in thumb). However, the very voice we sought can be over-done, thus distorting the voiceless into a voiced consonant (p, t, k, f, s, and sh become b, d, g, v, z, and zh). For those with a larynx, the difference between a voiced or voiceless consonant can be felt by placing a finger on the side of the larynx/voice box while saying the sound. (See previous articles noted below) There's a vibration that can be felt for the voiced, but not the voiceless sounds. When everything becomes voiced (as often happens in esophageal speech), the resulting faulty sound pattern can resemble pseudo bulbar palsy or inebriated speech. Correcting it lies not in dropping voice, but in adding more pressure to the sound emerging from the lips when making the voiceless sounds. When learning esophageal speech, a moist finger, strip of Kleenex or whistle placed at the lips may help the laryngectomee speaker monitor the extent to which pressure is exploded from the mouth when talking. Voiceless consonants have more air power! One nasty voiceless consonant is the 'h' which baffles all laryngectomees. To avoid sounding like a Cockney from England, we borrow from another country. 'I' ('ich' in German) uses a prolonged kiss of the back of tongue against the roof of the mouth. The same sound is in Scotland (loch/lake). We get the same result by saying 'k' as a non-stop prolonged consonant: for the good esophageal speaker, saying the word 'hair' lies between 'air' and 'care'. Finally, three sounds are supposed to go through the nose: 'm, n, ng' as in the word 'morning'. The back part of the mouth (palate) must lower, letting sound and air into the nose to get the nasal tone. Some esophageal speakers don't let the palate down when making 'm, n, ng.' This common error makes the word 'morning' sound like 'bordig.' Again we may invoke a wet finger, this time placed just underneath the nose to feel whether air escapes nasally on these sounds.

What's In Store

The outlook for the continued use of esophageal speech is grim, at least in the United States, but also in many other parts of the world. Esophageal speech is the least utilized form of alaryngeal speech. Although the ES Speaker is less dependent on things - no device to carry, no prosthesis to insert, clean or replace - it takes longer to learn, has limitations of rate (fewer words per minute), takes more time to re-load air for speech, and has fewer physicians and SLP's who recommend it and even fewer who can teach it and trouble shoot problem cases. Although artificial larynx and tracheoesophageal speech (TEP) may cost more, these days, those costs are more apt to be covered by insurance or physician fees than SLP therapy sessions to teach esophageal speech. In addition, the preponderance of TEP success has lead to less teaching of esophageal speech in IAL clubs. Fewer IAL clubs and fewer IAL members portend a shift from peer support to highly specialized intervention.

Support for the continuance or existence of IAL Voice Institutes is eroding. Historically, the IAL Voice Institute has been a primary vehicle for training clinicians and laryngectomees how to train others in esophageal voice use. Few university programs in speech pathology include ES in the curriculum, at least not to the extent needed to prepare clinicians who are both confident and competent in offering this voice option.

Surgical specialization in voice restoration after laryngectomy is becoming a sub-specialty, even within the specialized field of ENT physicians. The role of ES can be expected to diminish more and more, at least in most parts of the world. Perhaps esophageal speech will continue to have a place in certain areas, although even this is not a guarantee.

Although we began with a focus on voices after total laryngectomy, we conclude by stressing speech and communication. This reinforces our goal of helping individuals cope with an unusual problem in living fully. Each of the three primary alaryngeal speech options ' AL, TEP, and ES' has advantages and disadvantages over the others. Although it has become rare given the current direction of alaryngeal voice rehabilitation, there will always be those for whom esophageal speech remains not only a viable option, but perhaps the best option. The question will be whether anyone can teach it to them. Or will they stumble upon it on their own as our Indiana Hoosier did several years ago.

VoicePoints: Are Your Voice And Speech "Fit"? (Part 1 of 2)

http://webwhispers.org/news/feb2004.htm

VoicePoints: Are Your Voice And Speech "Fit"? (Part 2 of 2)

http://webwhispers.org/news/mar2004.htm

Article from http://www.webwhispers.org/library/EsophagealSpeech.asp